The backbone of Britain’s motorway network was planned and built during the 1950’s, 60’s and 1970’s, but south of Avonmouth progress was quite slow, with a nine-mile M5 section between junctions 19 and 20 not seeing traffic until January 1973.

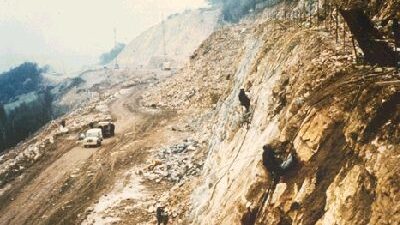

Since then, drivers here have marvelled at the work of the designers of the day, who, amongst several notable achievements, sliced a 33ft (11m) cutting deep into the Clevedon Hills’ limestone (above), creating the six-lane split-level dual carriageway still used today.

Junction 20 provides clues to one of several intriguing British motorway mysteries. Drivers today might rank events hereabouts as a remarkable folly, letting slip a great opportunity – or foundations for a long-dormant future opportunity. If you’re of a sensitive environmental persuasion you might feel the opposite applies in both cases, but here’s the story, judge for yourself.

This is a full-access intersection, notable for a roundabout amongst the motorway’s biggest – yet with just one solitary exit, serving the small town of Clevedon. Experienced motorway observers might recognise far greater design capacity here than traffic demands even today, over forty years after it was built.

Continuing southbound, note how the two carriageways diverge, and the lanes seem wider – while the central reservation has grown very wide indeed. Six miles later, junction 21 offers escape to the fading Victorian splendour of Weston Super Mare, after which normal lane and central reservation width resumes. Intriguingly, this junction is involved in a separate mystery – but that’s a story for another time.

Over twenty miles north-west, approaching Ashton Gate on Bristol’s south west fringe, a complex high level interchange and part dual-carriageway link network begins. Executed in grim 1960’s concrete, for the unfamiliar it’s a navigational nightmare, interconnecting two B roads, the A4 and A38, and several urban routes.

It also links traffic from the A370 Brunel Way, which points tantalisingly towards Weston Super Mare… marking the end of a stillborn dream. A mile south west from here this road becomes the Long Ashton bypass, another 1960’s project, built with more in mind than easing congestion in a village community. Today its a curious retro-hybrid: brief single carriageway, three lane road alignments, a viaduct, a short two lane dual carriageway stretch – is that space for a hard shoulder as well? – book-ended by two over-engineered, grade-separated junctions. After a couple of miles it ends abruptly, and the A370 resumes its windingly tortuous way south west.

These apparently unconnected pieces of highway engineering all relate to the same fifty-year old puzzle, begun when Somerset County Council held regional highways responsibility to the Bristol city boundary.

Major roads then were largely planned on a so-called “predict and provide” model, as the 1960’s were becoming the golden age of the car. Somerset’s planners anticipated significant future traffic growth in both directions from south Bristol towards Exeter – and especially Weston Super Mare, where much new housing was expected.

A new high-capacity road linking south Bristol and the planned but then unbuilt M5 motorway route thus entered Somerset’s plans. Its line ran from Bristol’s Ashton Gate, including a new bypass for Long Ashton village, before striking away across country, passing just north of Nailsea, ultimately meeting the motorway line at what became Junction 20, the Clevedon interchange. The Long Ashton section was completed before the motorway arrived – and the route onwards to the M5 was protected from building until well after the motorway opened, but nothing else was ever constructed.

The full traffic calculations and rationale underpinning development of this scheme presumably rest deep in some Somerset dusty archive: no relevant files surfaced in the limited research time available.

However a pretty convincing case must have existed, predicting vehicle numbers sufficient to influence national motorway planning. Why? Well here, the vast, underused Clevedon interchange and wide carriageways and central reservation between J20 and J21 fall into place. When eight-lane motorways were unheard of in Britain, between these junctions the M5 came off its 1960’s drawing board ready to upgrade to four lanes in each direction – once the Somerset scheme was finalised.

Why was this south Bristol motorway spur not built? Local government reorganisation in April 1974 saw the newly formed Avon County Council take over highway responsibility in this region.

What Somerset had seen for years as a compelling case cut much less ice with Avon, which sidelined the project. ‘Predict and provide’ traffic assessment techniques later collapsed in disarray as major road-building funds evaporated – and a new, greener, much less car- friendly imperative came speeding over the horizon. Road-building cash and political will have been lacking ever since.

Today, there’s still no high quality south-west bound exit from Bristol, though significant house building is now moving forward in the region, especially around Weston Super Mare, where an employment and housing imbalance makes increased commuting inevitable.

In looking ahead to 2031, the 2006 Greater Bristol Strategic Transport Study forecast a need for a new south Bristol to M5 link – as “a long term measure.” An Ashton Gate to M5 J20 link was rated worthy of investigation – alongside one (longer) alternative, passing Bristol International Airport, where 10m passengers annually were predicted.

While road status wasn’t mentioned, at 2005 prices, this longer route had indicative build costs around £129m: the South Bristol Spur came in around £70m. An M5 upgrade to eight lanes between J20 and 21 wasn’t mentioned: that’s another entirely very costly matter.

These are serious numbers, but drivers, residents and commuters alike will testify that congestion in the south Bristol region isn’t going away, and inadequate roads lie at the root of its problems. There’s an old saying: what goes around comes around, so maybe the time is finally approaching for the south Bristol motorway spur.

Almost 50 years after first entering play, could this yet turn out to be the most delayed motorway link project in British road-building history?

If you’d like to know more about the background to the unbuilt Bristol motorway spur, have a look at:

http://www.ciht.org.uk/motorway/m5twedscheme.htm

http://www.wringtonsomerset.org.uk/locgovt/publications/gbstsreport.htm

http://www.pathetic.org.uk/unbuilt/weston_spur/

http://www.pathetic.org.uk/unbuilt/south_bristol_spur/

http://www.sabre-roads.org.uk/wiki/index.php?title=A370

http://www.westofengland.org/transport/gbsts

Dave Moss has a lifetime connection with the world of motoring. His father was a time-served skilled engineer from an age when car repairs really meant repairs: he ran his own garage from the 1930's to the 60's, while Mum was the boss's secretary at a big Austin distributor. Both worked their entire lives in the motor trade, so if motor oil's not in Dave's blood, its surely a very close thing.

Though qualified in Electronics, for Dave it seemed a natural step into restoring a succession of classic cars, culminating in a variety of Minis. Writing and broadcasting about these, and a widening range of motoring matters ancient and modern, gathered pace in the 1970's and has taken over since. Topics nowadays range across the modern motoring mainstream to the offbeat and more arcane aspects of motoring history, and outlets embrace books, websites national and international magazines, newspapers, radio programmes, phone-ins and guest appearances. Spare time: hard graft on the garage floor attending to vehicles old and new. Latest projects: that 1968 Mini Cooper S has finally moved again after 30 years, and when the paint is finished, the 1960 Morris Mini 850 will also soon be ready for the road again...