The long history of motoring includes some pretty notorious legislation to control and regulate roads, vehicles, and their drivers – and this Christmas, one of the more contentious moves of modern times is quietly celebrating its 50th anniversary.

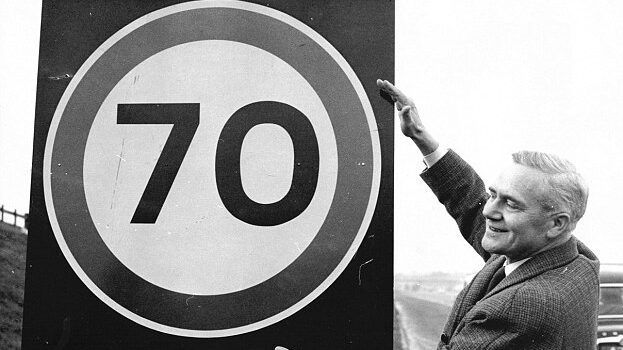

On 22 December 1965, with the best of Government intentions, British motorists found themselves under a blanket 70mph speed limit on all roads without an existing lower limit.

The story began after the October 1964 general election, which saw new Prime Minister Harold Wilson leading a Labour administration with a wafer thin majority – and an ambivalent attitude to motoring.

Scottish-born MP Tom Fraser was installed as Minister of Transport, replacing Ernest Marples, whose rock-bottom reputation amongst motorists had brought the slogan “Marples must go” into wide public circulation.

Fraser – having piled still more cuts onto the Beeching railway closures – seemed set on a similar course when, in early November 1965, parts of southern England, including much of the M1 motorway, became shrouded in fog.

With no illuminated warning signs, and hopelessly inadequate vehicle rear lighting by today’s standards, drivers continued at undiminished speed, and several serious multi-vehicle pile-ups followed.

On 24 November, Tom Fraser fielded questions in the House of Commons. Morris Edelman MP wanted to know “what further action he is taking to prevent collisions on the M1 in conditions of fog…”

The Minister said he was pressing on with a comprehensive study of signalling systems, to decide what permanent arrangements should be adopted on motorways, and two main measures were to be introduced.

First, an advisory 30mph speed limit would be temporarily applied during serious hazards like fog or other bad weather conditions.

Vertical pairs of alternately flashing amber lights would indicate this limit, placed one mile apart along the motorway and at entry points, switched on and off by police as conditions demanded. The Minister planned to have the system ready for operation on motorways by Christmas 1965.

The second measure seemed to have little to do with fog, but was destined to change the way of British motoring life for decades to come… “There will be a general speed limit of 70mph on motorways and all other unrestricted roads, for an experimental period of four months from Christmas until after Easter,” said Mr Fraser.

“This should diminish speed differentials, and thus lead to a reduction in accidents. The results will be carefully analysed by the Road Research Laboratory as the experiment proceeds.”

“These measures,” he continued, “are designed to improve driver discipline on motorways and other roads throughout the country. I hope they will be accepted in this spirit, because safety – first and last – is the inescapable responsibility of every individual driver.’

Later he told the press “This experiment has been virtually forced on us by the behaviour of an irresponsible minority of drivers, who are a danger both to themselves and everyone else. But if it is a life-saver it will be worthwhile.”

It was Tom Fraser’s first and last big announcement as Minister of Transport. The temporary 70mph limit began at noon on 22 December 1965: the very next day Tom Fraser was relegated to the back benches. He resigned his seat two years later.

Harold Wilson’s next Transport Minister was Barbara Castle, who made a much greater impact, eventually rivalling Ernest Marples as a target of motorists’ ire. The 70 limit experiment was to end at midnight on 13 April 1966: Barbara Castle extended it until 12 June, explaining to the House of Commons that so far there was no complete proof of the value or otherwise of the limit versus the earlier situation.

A month later she remained unconvinced. “The case is not proven, she said, “but there are signs, which I dare not ignore, that the speed limit has helped to reduce accidents, and therefore I should continue the experiment in its present form, but for a really effective period.

The Road Research Laboratory felt it needed at least 18 months for worthwhile results, and at the time Mrs Castle was about to introduce another experiment which also became permanent – banning heavy vehicles from the third lane of three-lane motorways. This was to run for 15 months from 23 May 1966, so the 70 limit experiment was extended to match it, with both ending on 3 September 1967 but there was opposition as recorded by Pathe News.

On 12 July, almost 19 months after the 70mph limit began, Mrs Castle told the house that the Road Research Laboratory analysis was complete. “It estimates that, in 1966, motorway fatalities and casualties were 480 less than would have been expected without the speed limit, a reduction of about 20 per cent – including 58 fewer people killed. Also, on a 73-mile length of the M1, M10 and M45 during the trial, the accident rate was the lowest recorded -10% below the average for the previous five years. The proportion of injury accidents was also the lowest recorded.”

The report also found that main road accidents were around 3½ per cent lower than expected without the limit. Reductions in fatal and serious accidents and casualties were lower on dual carriageways, while the effect on single carriageways was uncertain, since 70mph was (in 1966) possible on relatively few of them.

Mrs Castle said she accepted the Road Research Laboratory results clearly established the 70mph limit reduced motorway casualties. Despite wide consultation, “None of the arguments advanced against the limit convinces me we should forgo this saving of life and injury,” she said.

“I am perfectly satisfied that, in the face of this evidence, I would be failing in my public duty if I were now to abandon the 70 mph speed limit. I have, therefore, decided to continue it indefinitely on motorways.” And, 70’s fuel crises apart, that’s the way it has stayed since September 1967…

The 70 limit was also initially retained for single carriageway roads, though a national 60mph limit was introduced in 1977.

References

Wikipedia item on the history of British speed limits

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Road_speed_limits_in_the_United_Kingdom

A biography of Tom Fraser, including his time in Parliament, is here

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tom_Fraser

The detailed legislative story of the 70 Motorway limit and the later 60mph single carriageway limit can be traced via speeches, statements and questions in the House of Commons through Hansard. The search facility is available here:

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com

All Tom Fraser’s contributions in the House of Commons are indexed here

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/people/mr-thomas-fraser

All Barbara Castle’s contributions to the House of Commons are indexed here:

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/people/mrs-barbara-castle/

The actual announcement of the 70 limit becoming permanent is here (along with subsidiary questioning by MP’s following the announcement)

There were widely differing opinions and views on the introduction of the 70mph limit. Some of them were reported in the pages of the Times newspaper:

‘Saving motorists from themselves’ The Times, p16, 11th November 1965.

‘Most Drivers Stay Within 70 MPH Limit’ The Times, p8. 23rd December 1965.

‘More Experience Needed’ The Times, p13, 7th April 1966.

’70 M.P.H. limit for another 15 months’ The Times, p1, 18th May 1965.

’60 M.P.H. limit for some roads?’ The Times, p1,13 July 1967.

‘Effectiveness of 70 mph limit’ The Times, p15, 7th November 1967.

Dave Moss has a lifetime connection with the world of motoring. His father was a time-served skilled engineer from an age when car repairs really meant repairs: he ran his own garage from the 1930's to the 60's, while Mum was the boss's secretary at a big Austin distributor. Both worked their entire lives in the motor trade, so if motor oil's not in Dave's blood, its surely a very close thing.

Though qualified in Electronics, for Dave it seemed a natural step into restoring a succession of classic cars, culminating in a variety of Minis. Writing and broadcasting about these, and a widening range of motoring matters ancient and modern, gathered pace in the 1970's and has taken over since. Topics nowadays range across the modern motoring mainstream to the offbeat and more arcane aspects of motoring history, and outlets embrace books, websites national and international magazines, newspapers, radio programmes, phone-ins and guest appearances. Spare time: hard graft on the garage floor attending to vehicles old and new. Latest projects: that 1968 Mini Cooper S has finally moved again after 30 years, and when the paint is finished, the 1960 Morris Mini 850 will also soon be ready for the road again...