Time now for reflection on a very major event indeed… 60 years ago, on the 21 September 1955, the modern age of road transport in Britain got into gear.

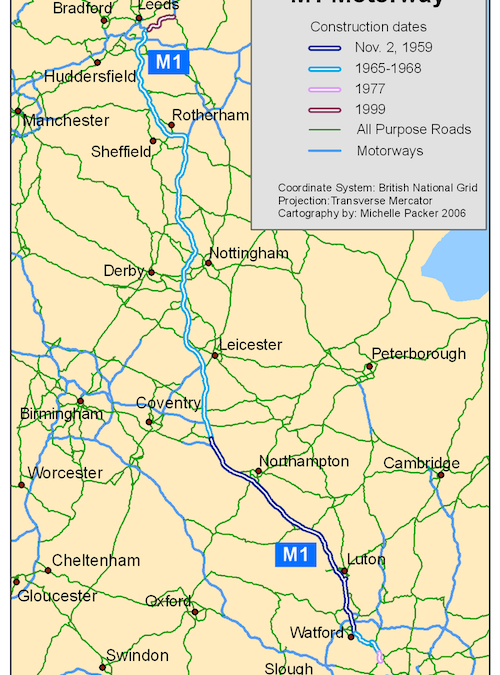

Minister of Transport, John Boyd-Carpenter, announced the line of a London to Yorkshire motorway on an entirely new route. It had no road number then – and it later emerged that behind the scenes, officialdom was arguing over quite how Britain’s road numbering system should embrace the coming motorway age. It was to become the M1.

Bearing in mind how long it can take to get even a mile or two of new road built today, and the alleged cost of filling in an odd pothole, its interesting that the minister expected construction to begin just two years after his announcement, with completion during 1959 – at an anticipated cost of £15m.

Unusually by modern standards, of the planned 67 motorway miles, the Ministry of transport was directly responsible for only 53, north of what’s now junction 10.

This included a motorway spur joining the A45 Coventry road near Dunchurch “providing a link for Birmingham traffic…” and ended two miles further north near Crick Northamptonshire at today’s Junction 18. Another 14 miles of motorway south of junction 10 was Hertfordshire County Council’s responsibility, with a new St Albans bypass and the M10 spur, taking the road to its southern terminus at the time – now Junction 5. The motorway was to have “two carriageways 36ft wide, separated by a central reservation, flanked by verges containing a hardened strip for emergency use.. It will be designed to carry traffic safely at 70mph, with a flow of 30,000 vehicles a day in each direction.” The plans included six intersections, 46 bridges over public roads, eight railway bridges, three canal bridges, five river bridges – and plenty more for footpaths and private and agricultural access.

Consultation followed, with anyone able to make representations to the minister, or lodge objections, until 24 December, but researching the story 60 years later the impression lingers that this road was going to be built, representations or not.

A spokesman for the joint committee of the RAC, the AA and the Royal Scottish Automobile club was quoted in The Times newspaper the following day, saying the announcement marked… “What we hope will be a new and more enlightened era in Britain’s road policy. It is more than 20 years since any large scale project of this kind has come so close to reality.”

It continued, “The very fact that this relatively modest scheme (Ahem, about 67 miles of new motorway, built from scratch to an entirely new design in four years – on an entirely new route…) has created so much interest, is a fair commentary on the deplorable neglect of the country’s road system since the war.”

One can only wonder what the committee might have regarded as a major scheme or the reaction to similar proposals today and how long it might now take to decide on a route, let alone complete the work. Comparisons to the HS2 project come to mind.

Also in 1955 –

Average wage was £9.25p a week.

Fish fingers were introduced by Clarence Birdseye, milk was 3p a pint, a loaf cost 4p and a pound of butter was 18p.

Beer was 9p a pint, cigarettes cost 18p for 20 and petrol was 22.5p a gallon (4.5 litres).

Moss won the British GP at Aintree.

The first Airfix model was introduced, a Supermarine Spitfire.

The average house cost £2,064 but a three-bed Somerset farmhouse with 48 acres went for £6,500.

Interest rates were 3.75%.

ITV was launched on 22 September 1955.

Government ploughed an unprecedented £1.2 Billion into rail electrification.

vChurchill resigned and Eden won the General Election.

Tenders for four motorway construction contracts, each involving between 12 and 16 miles of road, were invited in September 1957.

An additional contract covered the southern section, including the St Albans bypass, for construction to similar standards in a similar time.

This was let to Tarmac Civil Engineering Ltd, while John Laing and Son Ltd gained the remaining four contracts. Work began on 24 March 1958, with completion planned just nineteen months later in October 1959. Translated into work on the ground, the task and its logistics were as spectacular as the road itself.

Building 67 motorway miles in this timescale required an average of one fully completed mile of dual carriageway every nine working days – in turn requiring construction of one bridge every three days. The workforce comprised over 3000 men at its peak, using over 1000 major items of road-making equipment.

The summer and Autumn of 1958 was wet… very wet, but work went on, often for 22 hours at a stretch; within 13 weeks around 7.5 million tons of earth had been moved – reportedly half the total necessary, leaving the line of the road clear.

Six months on, 120 of the 132 necessary bridges had been started, 40 were finished, and 85% would be complete by Christmas – and ten miles of concreted carriageway was already in place.

Even as the new motorway neared completion, controversy surrounded proposals for the second section, running between Crick and Doncaster. Two proposed routes fell foul of vociferous objections through either visual intrusion or prime agricultural land take: one route through Charnwood Forest resulted in an opposition petition signed by 30,000 people. The project was saved by Leicestershire County Council: it proposed compromise modifications to the 83 mile route which were found agreeable, and the route suggested then remains in use today.

Not even the worst of Britain’s notorious weather delayed the opening of the first section of the London to Yorkshire motorway on 2 November 1959 after superhuman efforts by the contractors, designers and engineers involved.

The Preston bypass was completed the previous year and became the country’s first motorway-standard road – but this was Britain’s first genuine long distance motorway.

Incoming Minister of Transport Ernest Marples opened the still un-numbered road, paying special tribute to his predecessor, Harold Watkinson.

Today’s motorists owe a certain gratitude to this now forgotten Minister who between 1955 and 1959 did much to promote and enable Britain’s post war road improvement programme, paving the way for the motorway age as we know it.

Nor is Watkinson alone as a long forgotten man of the moment: Sir Owen Williams, consulting engineer on the London-Yorkshire project, left behind a sometimes controversial but particularly vital legacy for British motorists. Nowhere was his remarkable and enduring work more visible than on this new motorway, though the Western Group region also benefited from his considerable talents. But that’s a story for another time.

References

http://www.ukmotorwayarchive.org/ A comprehensive and detailed archive operated by the Motorway archive Trust: To find out more about the construction of the earliest sections of the M1, Select M1 Hendon to Crick on “search motorways.” The section on Crick to Doncaster is also listed, and available from the Hendon to Crick page

The full (and extensive) archive for the M1 roadbuilding scheme is stored at the Northamptonshire CC Record Office. Reference number is MA/ER/M1/ and Accession number 2003/86

The equally extensive John Laing archive is now held by Historic England. Contact via http://www.historicengland.org.uk/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harold_Watkinson,_1st_Viscount_Watkinson

Wikipedia entry for Harold Watkinson; He is also listed in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

http://www.cbrd.co.uk/motorway/m1 Provides an analysis of M1 from current and historical perspectives.

There was extensive coverage relating to the start of the motorway age and the building of the first section of the M1 in The Times newspaper between 1956 and 1960.

There are many files concerning the enabling legislation, and other government papers relating to the period before and after Britain’s motorway network became a reality in the National Archives at Kew.

http://www.icevirtuallibrary.com/content/article/10.1680/iicep.1961.11409

Discussion document on the overall project from the Institution of Civil Engineers dating from 1960

Books and publications

Building the Motorway network – The South East and East Regions

Authors: Sir Peter & Robert Baldwin and Dewi Ieuan Evans. Pub Phillimore and Co, 2007. (ISBN: 13-978-186077-44611)

The Motorway achievement. Volume 1: Visualisation of the British Motorway System. Edited by Sir Peter Baldwin and Robert Baldwin ISBN 978-0-7277-3196-8.

Pub: Motorway Archive Trust.

Provides a set of contrasting first hand accounts of the creation of the motorway system, the problems encountered, the solutions adopted and the lessons learned for future motorway development.

The General Motorway Plan, John Frederic Allan Baker, (1960), Institution of Civil Engineers, London. ICE Proceedings, Volume 15, Issue 4 April 1960, pages 317-332.

http://www.icevirtuallibrary.com/content/article/10.1680/iicep.1960.11818

A History of the British Motorways, George Charlesworth,

(1984) Thomas Telford, London. ISBN: 9780727701596

Motorways, James Drake, H L Yeadon and D I Evans, (1969), Faber and Faber: London.

The London-Birmingham Motorway, L.T.C Rolt, (1959) Pub: John Laing.

Driving Spaces: A Cultural-Historical Geography of England’s M1 Motorway

Author: Peter Merriman ISBN: 978-1-4051-3073-8

October 2007, 320pp, Pub: Wiley-Blackwell

Available direct from

http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-1405130733.html

A largely academic journal, giving an insight across the whole range of factors involved in building a Motorway from scratch in Britain

© M1 route map created by Seaweege.

Dave Moss has a lifetime connection with the world of motoring. His father was a time-served skilled engineer from an age when car repairs really meant repairs: he ran his own garage from the 1930's to the 60's, while Mum was the boss's secretary at a big Austin distributor. Both worked their entire lives in the motor trade, so if motor oil's not in Dave's blood, its surely a very close thing.

Though qualified in Electronics, for Dave it seemed a natural step into restoring a succession of classic cars, culminating in a variety of Minis. Writing and broadcasting about these, and a widening range of motoring matters ancient and modern, gathered pace in the 1970's and has taken over since. Topics nowadays range across the modern motoring mainstream to the offbeat and more arcane aspects of motoring history, and outlets embrace books, websites national and international magazines, newspapers, radio programmes, phone-ins and guest appearances. Spare time: hard graft on the garage floor attending to vehicles old and new. Latest projects: that 1968 Mini Cooper S has finally moved again after 30 years, and when the paint is finished, the 1960 Morris Mini 850 will also soon be ready for the road again...